Reading Recommendations: Lady Lupin, Dorothy L. Sayers and Jane Austen

Dear listeners,

We have arrived at our final reading update of 2025! I hope you have enjoyed getting this monthly peek into what Leandra and I are reading while we are working on Shedunnit, and have been inspired to pick up a book or two yourself as a result. We're finishing strongly, with a mixture of classic literature, fantasy and, of course, crime fiction for you.

If you're interested in more reading content from us, I'll be doing my full round-up of every book I've read on my personal newsletter at the end of December — you can sign up for that here. Leandra is also talking about what she's read this year and her reading goals for next year on her YouTube channel.

Caroline Has Read: The Mystery at Orchard House by Joan Coggin

In December 2024, the Shedunnit Book Club selected as its monthly book Who Killed the Curate? by Joan Coggin. Both the book and the writer were brand new to me, and so was the series detective, Lady Lupin. I found this village Christmas mystery delightful, with the ditzy debutante Lupin simultaneously settling into her new role as an ordinary vicar's wife and trying to solve the murder of her husband's unpleasant curate.

I was thus very pleased to see that Galileo Publishers had this summer republished another of Joan Coggin's four Lady Lupin mysteries: The Mystery at Orchard House. This one was originally published in 1946 and is set on the eve of World War Two, three years after her marriage. This time, Lupin is not in her home village, but staying at a hotel in the Kent countryside for a two-week rest cure after being ill with influenza. She's there in spring, when the daffodils and apple blossom is out, so I think this would be a nice book to read at that time of year (we talk of summer mysteries and wintry/Christmas ones, but how many other seasons are represented?). Of course, during Lupin's stay at the hotel — which is run by an old friend who recently inherited it as a manor house and is now Making It Pay — she is drawn into the detection of crime via several petty thefts and an attempted murder. She's as scatterbrained and disorganised as ever, but remains charming and a fundamentally moral person, making her a good figure to follow through the mystery. The plot probably wouldn't win any awards for great originality or innovation, but since I tend to care more about quality of writing, character and setting anyway, this did not trouble me.

I'm taking part in Kate Jackson's "Reprint of the Year" awards this year, and this is the second of the two titles that I'm proposing for the prize. (The first was Not To Be Taken by Anthony Berkeley, read my thoughts on it here.) Do head over to Kate's blog and vote for it if you also enjoyed The Mystery at Orchard House this year! Joan Coggin is exactly the kind of writer I would never have discovered if it weren't for Galileo's republication of her mysteries, and I am very grateful to them for putting it out.

Caroline Will Read: The Documents in the Case by Dorothy L. Sayers and Robert Eustace

This is the next title coming up in the Green Penguin Book Club series! I'm looking forward to re-reading this co-written epistolary mystery (especially after doing a whole episode about this format, Death on Paper, earlier in the year). It's Sayers' only full-length novel not to feature Lord Peter Wimsey and the only one that she worked on with someone else. The episode will be out in the second half of January, so that's your deadline if you're reading along with me.

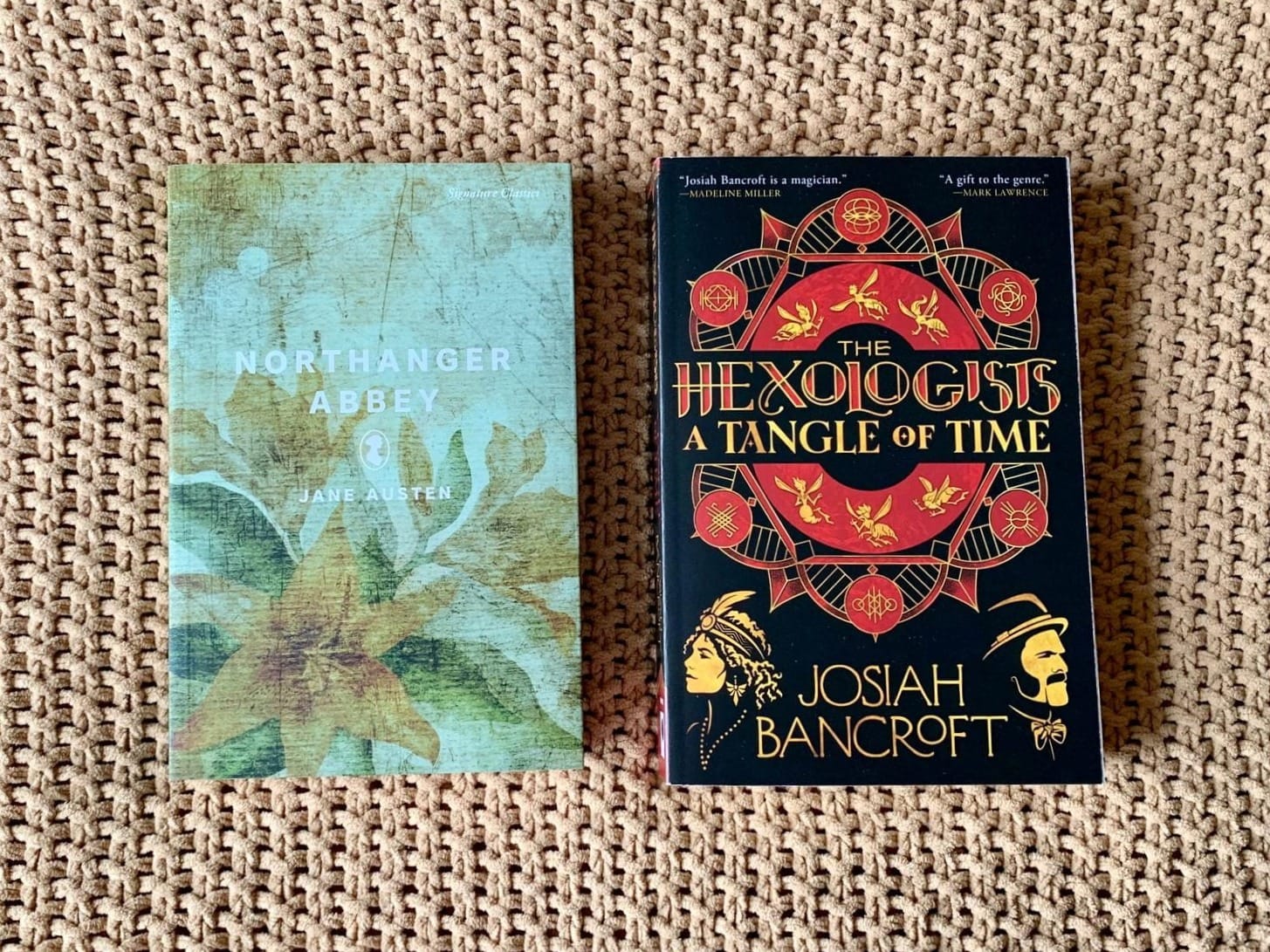

Leandra Has Read: Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

This was my first time reading Northanger Abbey. A friend gifted me a copy not long ago, and what finally motivated me to pick up this classic was the upcoming 250th anniversary of Jane Austen's birth. She was born on the 16th of December 1775, sharing a birthday with my father actually! Unbeknownst to me at the time of reading Northanger Abbey, this title was celebrating an anniversary of its own. Five months after Austen's death in July 1817, her brother and literary agent, Henry, published Northanger Abbey and Persuasion in a single volume in December of that year.

Catherine Morland was an absolute delight, and I loved the brief moments in which the narrator breaks the fourth wall to address the reader throughout our heroine's adventure. The book's tone reminded me of I Capture the Castle and Arabella, two other titles I have thoroughly enjoyed in the past. The most fascinating element of Northanger Abbey for me, however, was its rocky journey toward publication. Initially, it seemed as though it would be Austen's first published work, sold to Crosby & Co in 1803 for £10. The London bookseller proceeded to sit on the manuscript for over a decade as Austen published Sense & Sensibility, Pride & Prejudice, and so on. In 1816, the bookseller sold the book back to Henry for the amount they originally paid Austen, and the author jumped immediately into revisions. She died before she was able to finish the novel to her exact liking, but I would rather have some version of this story than none at all! It's officially my favourite Austen to date.

Leandra Will Read: A Tangle of Time by Josiah Bancroft

In December, I always have the goal of ending the year strongly with as many "easy win" reads as possible. That leads to a lot of mood-reading! Recently, my mood led me to start the sequel of Josiah Bancroft's fantasy mystery novel, The Hexologists, and it feels wonderful to be back with this sleuthing couple, Isolde and Warren Wilby. This time around, Is and War are investigating the mysterious death of an artist who reached out to Is not longer before she died. I'm excited to see just how much of the art world we see in this mystery. If you enjoy fantasy mysteries like The Witness for the Dead or the Sherlockian reimagining The Tainted Cup, then I highly recommend you add The Hexologists to your TBR. Hopefully I will be able to say the same for its sequel!

That's us for now! What are you planning on reading over the next few weeks? If you get some downtime over the festive period, do you line up a particular kind of book, or just see what you might receive as gifts? Let us know by replying directly or by leaving a comment to join the conversation with other readers.

Until next time,

Caroline

Some book links are affiliate links, meaning that the podcast receives a small commission when you purchase a book there (the price remains the same for you).