Reappraising Anthony Berkeley

A closer look at the Detection Club co-founder.

Dear listeners,

As fans of golden age detective fiction, we have lots of reasons to feel grateful to Anthony Berkeley. The success of his crime fiction during the interwar period assisted in propelling the genre to new heights of popularity. He created highly visible examples of mystery tropes that we now consider standard: the amateur sleuth, the first-person howdunnit, and the multiple solution mystery. Plus, he was a co-founder of the Detection Club and an influential reviewer of detective fiction. He might not be one of the most famous or well-read authors from this period today, but he did a great deal to ensure its longevity.

In this capacity, he has cropped up a fair bit on Shedunnit over the years. When we were doing research in the archive for this newsletter, I was surprised to see that almost all of the episodes devoted to Anthony Berkeley also feature Martin Edwards — current president of the Detection Club, long time friend of Shedunnit, and a keen Berkeley fan. When I first started making the show, I was relatively unfamiliar with Berkeley's work and unsure of becoming better acquainted with it, having been put off by the unsavoury misogyny on display in his 1926 novel The Wychford Poisoning Case. I had read that book because of its connections to the Florence Maybrick case (an early subject of the show) and wasn't especially anxious to spend much more with its author. But Martin convinced me that there was much more to Anthony Berkeley as an innovator in the field of interwar detective fiction and I persevered. And thank goodness I did! Some of the most thrilling "he did what?!" moments that I've had when reading crime fiction have come from his books. He may not have had a Christie-esque long career, but he certainly packed in the surprises.

Back in 2020, Martin was my guest for an episode titled The Psychology of Anthony Berkeley, in which he freely acknowledged that Berkeley can be a hard author to love:

"I think that Berkeley is one of those writers who will always be a bit of a Marmite writer. He's just a bit of a Marmite individual, I think. You like him a lot or you don't really get him. And I think that that was probably true in the thirties. It's certainly true now. But I think if you're interested in ingenuity, clever ideas, a touch of darkness because there's certainly a touch of darkness in his personality that comes through in books."

This is certainly the view that I've come to (and I do really like Marmite, so that tracks). Perhaps it's because Berkeley was a somewhat troubled, dark individual that he was able to be so interesting and original in his murder mysteries. His prickly personality didn't stop his work from being a hit with his fellow crime writers, who knew flair when they saw it, as Martin explained later in that same episode:

"Well, I think as a crime writer, he was hugely admired. Agatha Christie, I think, particularly admired his detective novels and she was a big fan. Dorothy L Sayers, too in the early days, although I also think that their personal relationship, had a few setbacks during the 1930s. He was a difficult customer and Dorothy probably wasn't the easiest either. So they had a slightly mixed time as friends. But I think that generally there is a huge amount of critical admiration for his work."

Berkeley took this mutual admiration and turned it into something concrete that endures to this day — The Detection Club. Martin explained how it came about in the episode devoted to the Club's history:

"His idea at that time was that detective novelists really didn't know each other socially at all, they were all working in isolation. And he thought it would be good to get together with fellow writers, and talk about matters of mutual interest, whether it was real life crimes of the day, whether it was their dealings with publishers or anything else... And the dinners were apparently a big success. And arising out of that success, he felt that it would be a good idea to form a social club that would meet a number of times a year to have dinner and essentially just chat and chat into the night. And so the club was was proposed. Dorothy L Sayers was amongst those who was an enthusiastic supporter, and she became very much a prime mover, but also Agatha Christie. Ronald Knox and a good many other leading lights of the day came on board.

By the end of the decade, though, Berkeley would have stopped writing detective fiction for good. His final work in the genre was published in 1939 and he did not ever return to pen more. How did Berkeley go from the enthusiastic co-founder of the Detection Club at the start of the 1930s to someone who never published a mystery again by the end of the decade? Martin has some ideas:

"I think were probably a mix of reasons. He said that he wasn't making enough money from the crime fiction. I'm slightly sceptical about that as an excuse. I think he lost his gusto. He wrote a letter in the late 50s or early 60s to a writer called George Bellairs, who's also published in the British Library series. And he said to Bellairs, in that letter, hang on to the gusto. Believe me, it goes and I think that that came from the heart. I think he just lost his enthusiasm, the desire, the energy that had kept him working very frenetically almost in the second half the twenties and through the 1930s when he did write a lot of books. And then I suspect mainly because of issues in his personal life, he just lost that zest and maybe had an extreme case of writer's block — that's been suggested to me by a family member. That was the impression that that person had. And it's hard to tell because he was quite secretive. But I think that one way or another, he lost his enthusiasm for writing fiction. Although he continued to enjoy reading it."

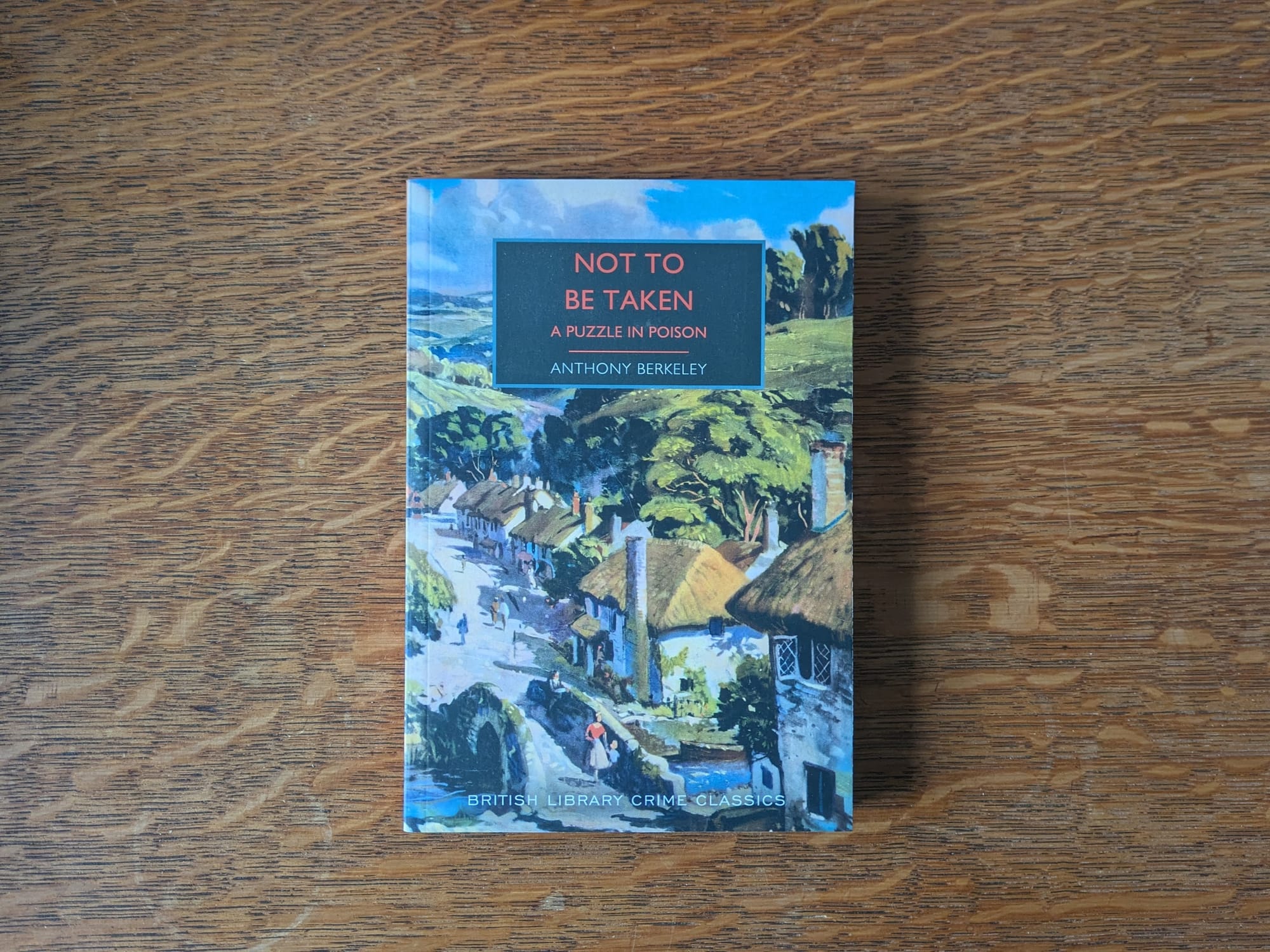

I've been very lucky that the years I have been working on Shedunnit have also coincided with a burgeoning reprint culture for golden age detective fiction. So many more books are now readily available than when I started the show back in 2018, among them many major Anthony Berkeley titles. If you would like to explore his bibliography, you no longer need to be very wealthy or very lucky in the secondhand bookshops or both. Several of these have appeared from the British Library Crime Classics imprint with introductions by Martin (and in the case of The Poisoned Chocolates Case, an entirely new additional ending to the story). Today, I want to draw your attention to one that was republished just this year, Not To Be Taken.

I'm delighted to be taking part in Kate Jackson's "Reprint of the Year" awards over at her blog this year, and this is the first of two titles that I'm going to be proposing.

Not To Be Taken is a standalone village poisoning mystery that first appeared in book form in 1938, having first been serialised as a competition mystery in John o' London's Weekly. Longtime listeners will know that I love a competition mystery, and did a whole live show about them at the International Agatha Christie Festival in Torquay a few years ago (listen to that here). As someone who adores the trivia and ephemera of the golden age almost as much of the books themselves, I loved that that this reprint also included Berkeley's original "report" on the competition entries as an appendix. No one person got the full solution completely correct, so he ends up dividing the prizes between a few promising contenders. Being able to read his commentary on the construction of the mystery and its clueing added greatly to my enjoyment of the book once I had finished it.

Although there are plenty of indicators in this book that we are in the late 1930s, rather than the halcyon days of the 1920s, in some ways this book was a return to familiar subject matter for Berkeley. It concerns an arsenic poisoning that is originally recorded as a natural death from gastric complication, only for an exhumation and investigation to be undertaken at the request of the deceased's brother. There is no prominent or recurring detective; rather the book is narrated by a local Dorsetshire farmer, Douglas Sewell, who diligently documents the toxic spread of gossip and suspicion through a small community. Those who are familiar with Berkeley's ability to write with drama and excitement — think Malice Aforethought or The Poisoned Chocolates Case — might find the tone of this book surprisingly subdued. But you just have to wait: it all makes sense in the end!

Both because of the cleverness of the story's construction and because the book includes the extra Berkeley material, I think Not To Be Taken is an excellent candidate for Reprint of the Year. If you agree, keep an eye on Kate's blog so that you can vote when the time comes! I'll be along with my second nomination in two weeks. Meanwhile, I hope you feel inspired to try or revisit some Anthony Berkeley, either via the podcast or by picking up one of his books.

Until next time,

Caroline

You can listen to every episode of Shedunnit at shedunnitshow.com or on all major podcast apps. Selected episodes are available on BBC Sounds. There are also transcripts of all episodes on the website. The podcast is now newsletter-only — we're not updating social media — so if you'd like to spread the word about the show consider forwarding this email to a mystery-loving friend with the addition of a personal recommendation. Links to Blackwell’s are affiliate links, meaning that the podcast receives a small commission when you purchase a book there (the price remains the same for you).