Did E.C. Bentley Predict The Golden Age in 1913?

A closer look at Trent's Last Case.

Dear listeners,

It's Green Penguin Book Club time again! And we have reached the eleventh crime, or green, title in the original Penguin series: Trent's Last Case by E.C. Bentley.

This book is Penguin 78 and joined the series in January 1937. It was originally published in the UK in 1913.

Here's my copy:

Joining me on the show to discuss this book are Flex and Herds, the Australian broadcasting duo behind the Death of the Reader radio show and podcast. If you haven't already listened to them deconstruct and try to solve classic murder mysteries on air, you have a treat in store for you.

The experience of reading and re-reading Trent's Last Case as I have done over the past couple of years is an interesting one. The Shedunnit Book Club read this book together in March 2024, and in advance of that I did a proper deep dive on it (including watching the somewhat patchy 1952 film adaptation starring Orson Wells). The book zips along with a fun, light tone no doubt drawn partly from E.C. Bentley's other work in journalism and in comic verse. Indeed, the whole conceit of the book — an amateur sleuth's first outing that we know before opening the book will be his "last case" — is humorous.

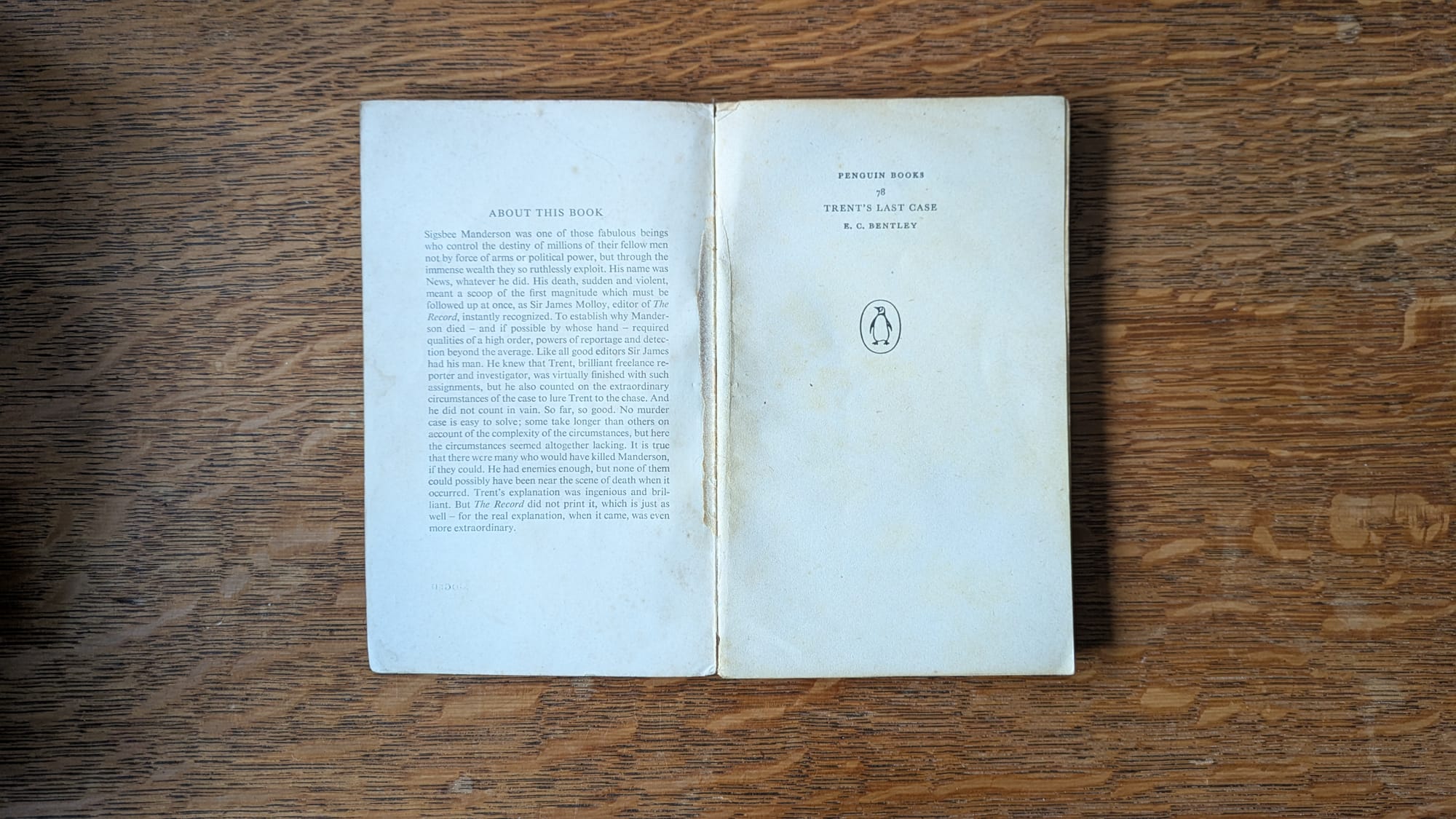

This is the blurb for the book that was printed on the inside front cover of my edition, which should hopefully give you a sense of what I mean. It's a little bit camp, but with some plot power too:

"Sigsbee Manderson was one of those fabulous beings who control the destiny of millions of their fellow men not by force of arms or political power, but through the immense wealth they so ruthlessly exploit. His name was News, whatever he did. His death, sudden and violent, meant a scoop of the first magnitude which must be followed up at once, as Sir James Molloy, editor of The Record, instantly recognized. To establish why Manderson died - and if possible by whose hand - required qualities of a high order, powers of reportage and detcction beyond the average. Like all good editors Sir James had his man. He knew that Trent, brilliant freelance reporter and investigator, was virtually finished with such assignments, but he also counted on the extraordinary circumstances of the case to lure Trent to the chase. And he did not count in vain. So far, so good. No murder case is easy to solve; some take longer than others on account of the complexity of the circumstances, but here the circumstances seemed altogether lacking. It is true that there were many who would have killed Manderson, if they could. He had enemies enough, but none of them could possibly have been near the scene of death when it occurred. Trent's explanation was ingenious and brilliant. But The Record did not print it, which is just as well - for the real explanation, when it came, was even more extraordinary."

Returning to Trent's Last Case again this year as part of the Green Penguin series, I was particularly struck by how extensively it seems to predict the tropes and motifs that were to become the backbone of the "golden age of detective fiction" a decade later. This book is full of fingerprint clues, red herrings, seemingly unbreakable alibis, a closed circle of suspects who all hated the murder victim, and more. If you told me it was published in 1933 rather than 1913, I would believe you.

It isn't just that this pre-WWI book contains many of the same features that would become popular in the mid 1920s. Bentley goes further: a lot of the time he is parodying these tropes, almost as if he is poking fun at a genre (the puzzle mystery) that doesn't properly exist yet. The other popular crime writers of the 1910s were Arthur Conan Doyle, L.T. Meade, G.K. Chesterton and Baroness Orczy, all of whom wrote mysteries that were more interested in suspense and surprise (or in Chesterton's case, moral philosophy) than they were in the interplay of amateur and professional detective as they hunt for clues. At times when I was reading the book again for this episode, I started entertaining bizarre time travel theories, in which E.C. Bentley had lived through the golden age of detective fiction and then jumped back to write its point of origin after the fact.

Nonsense, of course. There is a much better explanation for why Trent's Last Case feels like a murder mystery time capsule that wasn't opened until the 1920s. I think it reads this way because the principal authors in this genre post WWI were all obsessed with this book — they adored it, studied it closely, and then cherry picked its best bits to develop further their own work.

Agatha Christie called it "one of the three best detective stories ever written". Dorothy L. Sayers said that “It is the one detective story of the present century which I am certain will go down to posterity as a classic. It is a masterpiece.” Ronald Knox said that “I suppose somebody might write another story as good as Trent’s Last Case, but I have been waiting nearly twenty years for it to happen" and R. Austin Freeman commented that “the literary workmanship is of a quality that must satisfy the most fastidious reader.”

Because the stellar mystery writing careers of Christie and Sayers, if not the others, then went on to eclipse poor old Trent's Last Case, when we come at last to Bentley's book it feels like an oddity, rather than the explosive inspiration that it must have been in 1913. We can get a little sense, I think, of how meaningful this book was to the writers of the golden age of detective fiction from the fact that they insisted that E.C. Bentley take over from G.K. Chesterton as the president of the Detection Club when the latter died in 1936, even up until that year Bentley had only published the one mystery novel. He did follow up Trent's Last Case with Trent's Own Case that same year, 1936, and the Detection Club held a special gala dinner in the book's honour. Few, if any, other works got this treatment, as far as I know.

I hope that if you take this opportunity to spend some time with Trent's Last Case, you are able to enjoy it both as an important moment in detective fiction history and as a silly novel about haphazard sleuth who makes every possible mistake and then some. Because it is both, I believe, and should be appreciated as such.

The next book to get the Green Penguin Book Club treatment will be Penguin 79, The Rasp by Philip MacDonald. Look out for that episode in November!

Until next time,

Caroline

You can listen to every episode of Shedunnit at shedunnitshow.com or on all major podcast apps. Selected episodes are available on BBC Sounds. There are also transcripts of all episodes on the website. The podcast is now newsletter-only — we're not updating social media — so if you'd like to spread the word about the show consider forwarding this email to a mystery-loving friend with the addition of a personal recommendation. Links to Blackwell’s are affiliate links, meaning that the podcast receives a small commission when you purchase a book there (the price remains the same for you).